Sexual Health Care in Prostate Cancer Survivorship*

Learning Objective: At the conclusion of this continuing medical education activity, participants will understand the importance of attending to sexual health as an aspect of quality of prostate cancer survivorship care, recognize the impact of prostate cancer treatment on all aspects of sexuality, and be familiar with medical and psychosexual treatments to support sexual health of the patient and partner after prostate cancer treatment.

Nnenaya Q. Agochukwu, MD, MS

Disclosures: Nothing to disclose

and

Daniela Wittmann, PhD, MSW

Disclosures: Movember Foundation: Research Funding

Department of Urology

Dow Division of Health Services Research

University of Michigan Health System

Ann Arbor, Michigan

*This AUA Update addresses the Core Curriculum topics of Oncology – Adult and Sexual Medicine, and the American Board of Urology Modules: Oncology, Urinary Diversion and Adrenal, and Impotence, Infertility and Andrology.

Key Words: survivorship, sexuality, prostatic neoplasms

PROVIDING SEXUAL HEALTH CARE IN PROSTATE CANCER SURVIVORSHIP

Prostate cancer is the most prevalent male cancer in the U. S., with 1 in 7 men facing the possibility of being diagnosed each year. In 2017 a total of 161,360 men were diagnosed with prostate cancer and 3,306,760 men were living in prostate cancer survivorship.1 Cancer survivorship is defined as the period that begins at the time of cancer diagnosis and continues through treatment to the end of the survivor’s life.2 Today, prostate cancer is a chronic condition. Recognizing that patients were increasingly living longer with cancer, the National Cancer Institute established the Office of Cancer Survivorship in 1996 with the mission to “enhance the quality and length of survival of all persons diagnosed with cancer and to minimize or stabilize adverse effects experienced during cancer survivorship.”2 During the last 20 years the IOM (Institute of Medicine) has been advising on care in cancer survivorship with emphasis on the 4 major components of survivorship care of 1) prevention and detection of new and recurrent cancers; 2) surveillance for recurrent or new primaries; 3) interventions for late treatment effects in domains such as urinary, bowel and sexual function, fatigue and depression; and 4) coordination between specialist and primary care providers to fulfill survivors’ needs.3

Given that all cancers are different and have different consequences in survivorship, prostate cancer specific survivorship guidelines were established.4 While prostate cancer survivors, particularly those with localized disease, have a high rate of survival, life in survivorship can be challenging. Sexual side effects have been described as among the most significant bothersome symptoms for which men continue to seek solutions long into survivorship. Based on a cohort of 2499 Michigan survivors, sexual symptom burden was a topic for which they needed more information an average of 8 years after treatment.5

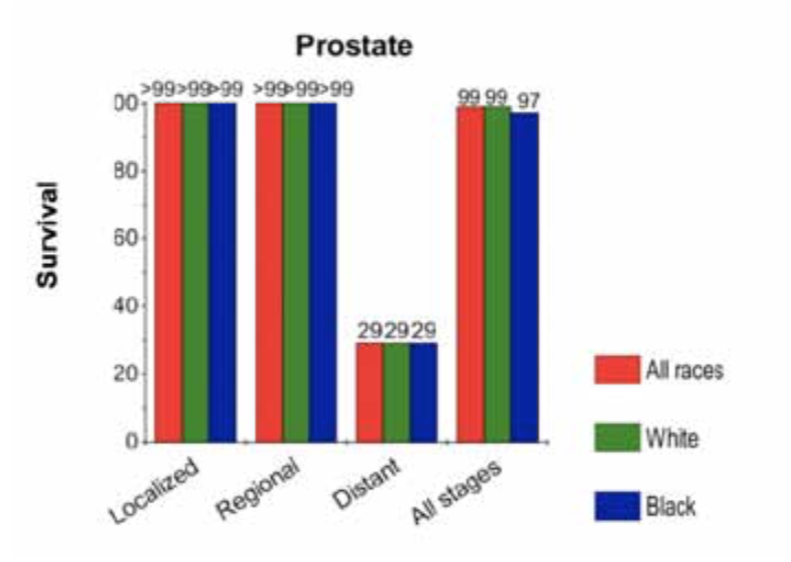

Sexual side effects of prostate cancer treatment. It is estimated that by 2030 prostate cancer will be the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in North America.6 Currently, average life expectancy after diagnosis is 22 years, and the average age at diagnosis is 67 years. The 5-year survival rate is illustrated in figure 1.1

Prostate cancer survival comes at a price, as most survivors experience a long-term symptom burden driven by the type of treatment received. Men treated with surgery experience immediate erectile dysfunction, orgasmic dysfunction, penile shortening and urinary incontinence. After radiation, men are at risk for a number of urinary and sexual side effects, such as dysuria, incontinence, frequency, urgency, progressive erectile dysfunction and diminishing semen volume. They are also at risk for fecal incontinence, blood in the stool and rectal pain. Hormonal therapy brings about more systemic changes due to loss of testosterone. Sexual side effects include genital shrinkage, low or no libido, erectile dysfunction, anorgasmia and diminished semen. Other side effects are loss of bone density, mood changes, fatigue, gynecomastia and body hair loss. Metabolic syndrome and cardiac issues also may develop in men on hormonal therapy (Appendix 1, online issue only).4 Sexual and physical changes after treatment can result in distress, depression, anxiety, relationship problems and difficulty managing social roles.

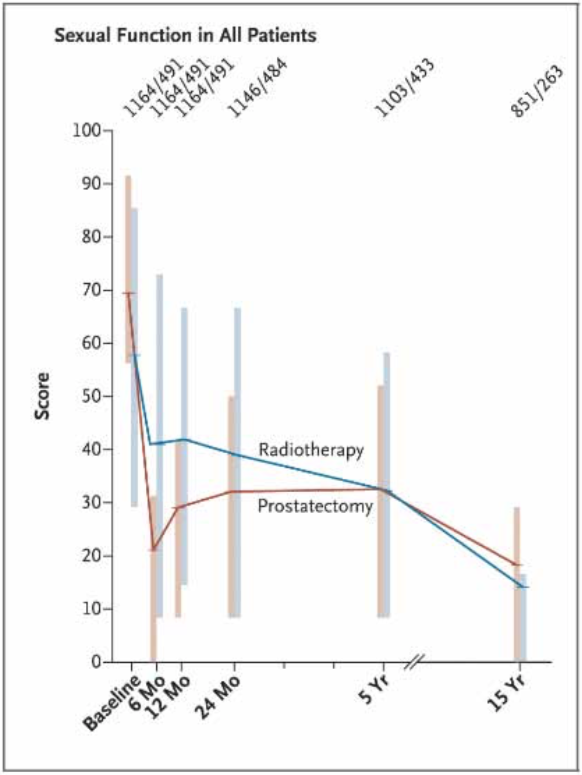

Sexual symptom burden after surgery and radiation. Many studies that document the impact of prostate cancer on sexual function include men treated with radical prostatectomy and radiation as both are definitive treatments (Appendix 2, online issue only). In PCOS (prostate Cancer Outcomes Study) urinary, bowel and sexual function outcomes were evaluated among men undergoing prostatectomy and radiation therapy in a 15-year period.7 The study included 1655 men, of whom 1164 underwent prostatectomy and 491 received radiation therapy. At 2 and 5 years men who underwent radical prostatectomy had higher odds (OR 6.22) of urinary leakage but at 15 years there was no significant difference between the groups. Men who underwent radical prostatectomy had higher odds of erectile dysfunction at 2 and 5 years (OR 3.46 at 2 years, 1.96 at 5 years) compared to their counterparts who received radiation. At 15 years erectile dysfunction was present in 87% of patients who underwent prostatectomy and 94% of those who received radiation therapy (fig. 2). The similar rates at 15 years are likely due to the additional impact of age on erectile function. Similar findings were noted in 1643 men enrolled in the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment trial in which 6 years after treatment men who underwent radical prostatectomy experienced the greatest decline in erectile function compared to those who received radiation or were under active surveillance.8

ABBREVIATIONS: ADT (androgen deprivation therapy), ED (erectile dysfunction), LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgen- der), PDE5i (phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors), VED (vacuum erection device)

In the Comparative effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and radiation study functional outcomes were evaluated in 598 patients who received external beam radiation therapy, 1523 who underwent radical prostatectomy and 429 under active surveillance.9 As in PCOS, at 3 years the radical prostatectomy group had the greatest decline in sexual function scores and bother compared to the external beam radiation therapy and active surveillance (when controlling for baseline sexual function) groups. Men on active surveillance also had ED at 3 years (51%), although it was less prevalent than in those who under-went definitive treatments, possibly due to the impact of age.

In a more recent study of 2354 men erectile function recovery was evaluated, taking into consideration advances in surgical and postoperative care, such as robotic surgery, refinement of nerve sparing radical prostatectomy technique and the introduction of penile rehabilitation programs, all thought to enhance recovery of erectile function.10 The patients were treated between 2008 and 2015, and only surgeons who performed 100 procedures or more were included in the study. After a decade potency outcomes did not improve and year of surgery was not associated with recovery of erectile function. This study highlights the likelihood that surgical technique improvements alone cannot improve outcomes. patient and partner characteristics, including sexual function, and comorbidities as well as availability of specialty support, such as sexual medicine physicians, physical therapists and sex therapists, may play an important role in achieving optimal outcomes.

Technological advances in radiation have allowed for administration of higher doses of radiation without added toxicity. Shaikh et al administered hypofractionated intensity modulated radiation therapy, an increased dose of radiation of shorter duration, to 151 patients who were compared to 152 patients treated with conventional intensity modulated radiation therapy, and there was no increase in patient reported urinary, bowel and sexual burden.11 It is important to note that radiation treatment for high risk localized prostate cancer now often includes hormonal therapy, which alters the sexual symptom profile.12

Sexual symptom burden after hormonal therapy. Androgen deprivation therapy is widely used to treat metastatic and biochemically recurrent disease, and is associated with adverse side effects (Appendix 1, online issue only). erectile dysfunction rates are estimated between 70% and 90% for men receiving ADT.13 Men also experience decreased libido, anorgasmia and decreased testicular size. These results are consistent with the results of the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor trial14 and PCOS, where 73% of 431 men receiving ADT ceased sexual activity and 69% of men who were potent before ADT were impotent after treatment, regardless of the type of ADT.15 According to a review by Fode and Sonksen, it is important to note that as many as 20% of men on ADT maintain some libido and erectile function.13

Other sexual dysfunctions and aging. Many studies on sexual dysfunctions following prostate cancer treatments focus on ED, and yet prostate cancer survivors experience other bothersome sexual dysfunctions, including climacturia, orgasmic dysfunction and penile changes, including penile shortening and de novo penile curvatures.16 These problems can lead men to avoid or feel less satisfied with their sexual relationships and can also decrease sexual function in the female partner.17

Sexual functioning generally trends toward decline after prostate cancer treatment and for most men it does not return to baseline levels.7 It is important not to overlook the general decline in function associated with age as up to 50% of men demonstrate some degree of erectile dysfunction preoperatively.18 Younger men may find psychological adjustment following treatment for prostate cancer more difficult as they likely did not have preexisting sexual problems.19 When considering sexuality in the survivorship period, it is important to account for not only baseline sexual function and changes in sexual function with treatment, but also the effects of age.

SEXUALITY IS A LARGER CONCEPT THAN SEXUAL FUNCTION AND DYSFUNCTION

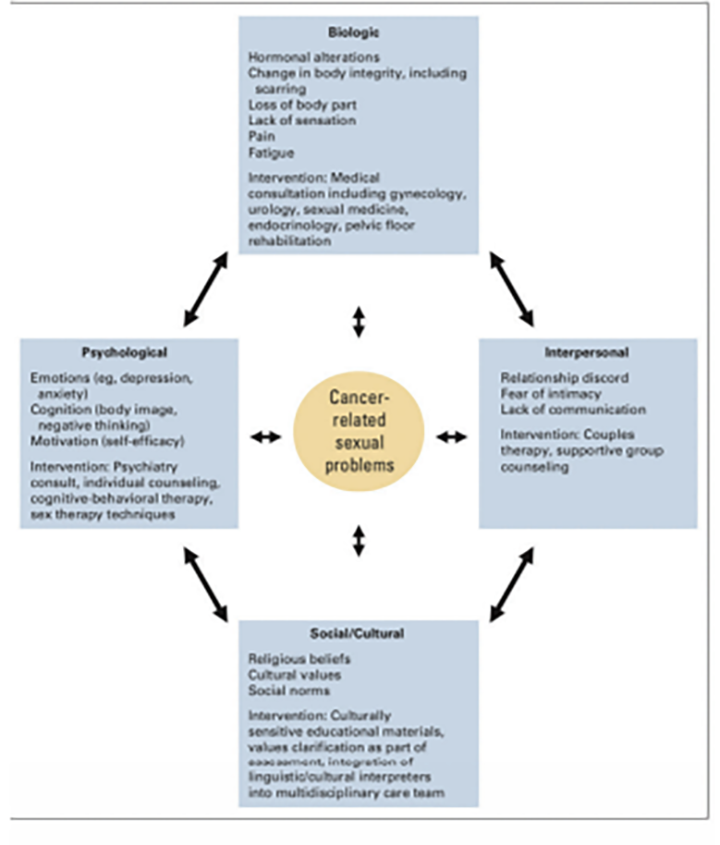

Sexual dysfunction following radical prostatectomy has impact beyond physiological changes. Bober and Varela delineate the psychological, relational and sociocultural domains of sexuality affected by cancer and its treatment (fig. 3).20 These biopsychosocial impacts are easy to understand if one attempts to step into survivors’ shoes. As men wish to continue to stay sexually active, they now need to rely on sexual aids to be able to engage in penetrative sex, which leads to loss of spontaneity and, for many men, feelings of loss of control over their bodies and sexual performance. Urinary incontinence or irritability, low libido, possible bowel dysfunction and fatigue may further interfere with sexual activity. Men have reported experiencing a sense of loss, disturbance in body image, diminished sense of masculinity and even social diffidence as a result of sexual dysfunction.21 Men on ADT have described having lost the lust for sex and ability to be a good lover.22 Wall and Kristjanson refer to “hegemonic masculinity,” a cultural demand that men be self-sufficient, physically strong and emotionally composed, as a contributor to men’s loss of confidence after prostate cancer.23 This loss of confidence likely contributes to treatment regret, anxiety and depression.

Research on partners of men with prostate cancer shows evidence of their distress as well. In a focus group study Sanders et al described partners’ feelings that they were not attractive when the men did not engage sexually due to insufficient communication about sex and reduced spontaneity.24 Tsivian et al found that 60% of female partners of 28 couples were bothered by the male partners’ climacturia and 36% reported that their own orgasm had changed.25 In a qualitative study of 10 patients and 9 partners by Wittmann et al partners described unmet sexual needs and uncertainty about how to approach the male partner who was anxious about post-prostatectomy sexual dysfunction.26 In most studies partners reported coping with the lack of sexual satisfaction by making sex less important or by focusing on the emotional aspects of their relationships.27 Only in the study by Wittmann et al did some partners report turning to masturbation to meet their own sexual needs.26 Much of the research literature has recognized that partners need support for their distress in the context of prostate cancer. Understanding the fact that partners may have unmet sexual needs and asking about how they are meeting them demonstrates the recognition that partners are equal stakeholders in the prostate cancer experience with sexual health support needs of their own.

As men and their partners navigate their sex lives after prostate cancer, they are required to develop new methodology for sexual intimacy because of the loss of spontaneity, men’s need to use sexual aids for erectile function, incontinence and changes in penis size. Most studies report that couples find this to be a difficult problem, citing a lack of skill to conduct conversations about sex.24

Emerging research on gay and bisexual men with prostate cancer highlights the fact that their sexual concerns have not been addressed. In survey studies they report that too often they are treated as if they were heterosexual which alienates them and precludes them from seeking help. In 2011 the IOM report on LGBT health described barriers to care as “lack of provider knowledge about LGBT needs and patients’ fear of discrimination in healthcare settings.”28 In 2016 the National Institutes of Health declared LGBT health a health disparity and called for research to enhance understanding of the health care needs of the LGBT populations.29 Current studies indicate that gay and bisexual men have many similar responses to the sexual side effects of prostate cancer treatment as heterosexual men, such as feelings of loss, challenges to their male identity, difficulties in communication about how to accommodate sexual changes and acceptance of sexual aids. However, there are also some important differences. Gay men require a firmer penis for anal penetration than is necessary for vaginal intercourse. The loss of ejaculate as an aspect of eroticism is particularly meaningful to gay men. Since gay men are more likely than heterosexual men to be single when they are diagnosed and treated, they may have less support, and concerns about dating with a cancer diagnosis and sexual dysfunction can become a significant hurdle to overcome.

However, gay men are more likely to be willing than heterosexual men to seek mental health or sexual health treatment. Some gay couples employ coping strategies not reported in the research on heterosexual relationships, such as willingness to open their relationships to provide partners with the ability to continue to experience optimal sexual pleasure.30 However, more research is needed to understand how gay and bisexual men wish to have post-prostate cancer treatment sexual concerns addressed and what interventions will be effective.

Recognizing the impact on the man, on his sexual orientation, on the partner and on the relationship is necessary to provide comprehensive prostate cancer survivorship care. While culture plays a significant role in sexual expression, currently research on men from different ethnic groups in the U. S. is insufficient.

INTERVENTIONS SUPPORTING MEN AND PARTNERS IN PROSTATE CANCER SURVIVORSHIP

Supporting men and partners in prostate cancer survivorship means that all aspects of sexuality must be addressed. Early studies emphasized biological methodologies aimed at promoting erectile function recovery. As the impacts of sexual dysfunction on the emotional well-being of men and partners has been clearly demonstrated, support for the psychological and couple aspects of sexuality has been developed and tested during the last 15 years. Interventions tailored to gay and bisexual men, and to men from diverse ethnic groups are undeveloped to date.

Biomedical interventions: penile rehabilitation. Penile rehabilitation was pioneered by Montorsi et al in 1997 as an early intervention designed to prevent corporal damage after prostatectomy.31 It is based on an effort to translate animal models to humans. These models connected smooth muscle apoptosis and fibrosis in penile tissue after cavernosal nerve damage to irreversible ED.32 Trials in rodents to reverse ED using phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors demonstrated a reduction in apoptosis and hypoxia, and prevention of veno-occlusive dysfunction.33 Strategies for men after prostatectomy have included low dose or on-demand PDE5i, intracavernosal injections, transurethral suppositories or gels, vacuum devices alone or in combination with PDE5i and penile vibratory stimulation.34

Fode et al reviewed the use of medications and devices, and concluded that there was little evidence to support penile rehabilitation as a methodology for the restoration of erectile function.35 A more recent Cochrane review supports this conclusion based on an evaluation of 8 randomized controlled trials of 1699 participants.36 Interventions evaluated included scheduled PDE5i versus placebo or no treatment, scheduled PDE5i versus on-demand PDE5i and daily PDE5i versus daily intraurethral prostaglandin E1 (alprostadil). When comparing scheduled PDE5i to placebo, scheduled and on-demand PDE5i had little or no effect on short-term self-reported potency. Compared to intraurethral prostaglandin E1, scheduled PDE5i appeared to result in slight improvement in erectile function. However, these results do not control for patient level factors, including age, nerve sparing, baseline erectile function and disease burden. While randomized controlled trials did not demonstrate benefit for spontaneous erectile function recovery, studies have demonstrated that VED users versus non-users did not achieve improved spontaneous erection recovery but reported a smaller decrease in penile size after radical prostatectomy.37

Men may garner some benefit in activation and attentiveness to sexual recovery from a penile rehabilitation program.38 However, the International Consultation for Sexual Medicine acknowledged that data are inadequate to support a specific penile rehabilitation regimen for the recovery of erectile function.39 The AUA guidelines on ED recommend that patients be informed that early use of PDE5i may not improve spontaneous, unassisted erectile function after treatment.40

Biomedical interventions: treatments for erectile dysfunction. It is important to distinguish penile rehabilitation from erectile dysfunction. The goal of penile rehabilitation is to preserve the health of the erectile tissue while patients are recovering from tissue/nerve injury as a result of the prostate cancer treatment, while the goal of ED treatment is to provide men with erections sufficient for penetrative sex.

Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of PDE5i in men with ED following radical prostatectomy. A meta-analysis of 8 trials on PDE5i (sildenafil, vardenafil, tadalafil, avanafil, lodenafil, mirodenafil and udenafil) versus placebo demonstrated that PDE5i were well tolerated and efficacious for ED treatment and also recommended early initiation.41 Greater responsiveness was associated with patients who had mild ED, higher dosages with longer courses of treatment and on-demand dosing. In the study of tadalafil after radical prostatectomy (REACTT trial) the impact of daily and on-demand tadalafil versus placebo for 9 months was evaluated.42 Although there was no improvement in unassisted erectile function, daily tadalafil was more effective for drug assisted erectile function for men with ED following nerve sparing radical prostatectomy. PDE5i were compared to placebo in 5 randomized, double-blind controlled trials after radiation treatment with positive results.43-47

Other treatments have included intraurethral alprostadil, intracavernosal injections, vacuum erection devices and combination therapy. Observational studies on intraurethral alprostadil revealed improvement in erectile function.48, 49 Similarly, intracavernosal injections (prostaglandin E or bimix/trimix) have been demonstrated in observational studies to be of potentially high efficacy as post-prostatectomy ED treatment.50 However, as many authors acknowledged, attrition in this treatment tends to be great, and men may need psychological support when learning to use intracavernosal injections.51 Early use of a VED was found to allow for early sexual intercourse and couple satisfaction.37 Combination treatments that have demonstrated effectiveness in observational and pilot studies are PDE5i with intracavernosal injections,52 with intraurethral alprostadil49 and with VED.53 Interestingly, compliance with a VED was higher than that of PDE5i in that study.

Although there is a tendency to think of penile prosthesis as the treatment of last resort, some men opt for it early as it provides them with reliable erectile function support. In a study on satisfaction and outcomes among patients receiving penile prosthesis or oral PDE5i penile prosthesis was superior to oral treatment in terms of erection parameters (frequency, firmness, penetration ability and confidence).54 Despite demonstrated efficacy of penile prosthesis, its use remains low, with rates of 2.3% for 15,811 men who underwent radical prostatectomy and 0.3% for 52,747 men who received radiation therapy.55 The AUA guidelines recommend that men should be given the choice of all erectile function treatment modalities, based on thorough education and understanding of the benefits and risks of each (Appendix 3, online issue only).40 The AUA expert panel notes that men can begin with any type of treatment regardless of invasiveness.

When patients present with a history of low testosterone before prostate cancer treatment, testosterone supplementation may be discussed based on clinical factors and patient preference. The AUA guidelines recommend that clinicians inform patients that there is inadequate evidence on the risk-to-benefit ratio of testosterone therapy.40 Testosterone supplementation is not recommended as a treatment for ED. It should be noted that the use of erectile aids alone is low.56 Combining the offer of erectile aids with psychosexual counseling has shown to be a superior approach to promoting and improving the uptake and adherence to the use of pro-erectile aids.57, 58

Psychosocial interventions. Psychosocial intervention studies for prostate cancer survivors have been presented in narrative reviews of studies focused on a variety of outcomes, intervention content and measurement parameters.59 All interventions have included an educational component to increase patient and partner knowledge about the sexual side effects of prostate cancer and sexual rehabilitation, although most programs are directed at men following radical prostatectomy or radiation. Early studies pursued sexual function improvement as a primary outcome but without efficacy.

Addressing couples has added a positive dimension for the use of erectile aids. In a randomized controlled trial of 57 patients after non-nerve sparing prostatectomy Titta et al reported that counseling for couples resulted in greater use of intracavernosal injections compared to controls.57 Chambers et al also noted that peer and nurse support for 189 couples versus usual care led to greater use of pro-erectile aids by men following radical prostatectomy.58 Other outcomes successfully affected by psychosocial interventions have been management of pretreatment expectations, couples’ relationship satisfaction, reduced sexual bother and partner acceptance that a man can have a satisfying sex life despite erectile dysfunction.60 Couples with a man on ADT who underwent pretreatment psychoeducation were more likely to retain sexual activity than controls.61 Preparation for the sexual challenges after treatment and inclusion of partners should become routine features of pre-treatment counseling.

As research tested interventions have not become available in usual care, telemedicine is emerging as a method for providing sexual health expertise in survivorship. Following the biopsychosocial model, these interventions emphasize increase in knowledge, symptom self-management, sexual communication and expansion of sexual repertoire to attain sexual satisfaction. Skolarus et al tested a symptom management intervention that uses interactive voice response to assess symptom burden in 566 men, and then tailors management and coping strategies based on the selection of the symptom the men wish to manage.62 Chambers et al reported the efficacy of peer and nurse telephone support for use of pro-erectile aids.58 Only 1 evidence-based intervention is available publicly, which was introduced by Schover et al who successfully implemented an intervention via the Internet.63 Based on their research, the website Will2Love includes video interviews with survivors and advice for men and couples regarding sexual recovery (Will2Love.com). Awareness of telemedicine sexual health resources can be particularly useful to a urologist whose practice does not include sexual health expertise. TrueNth is a Movember initiative aimed at guiding prostate cancer survivors through their journey. The website https://us.truenth.org is available for prostate cancer survivors and offers decision support, symptom tracking, live experiences of men with prostate cancer and general information about prostate cancer.

SEXUAL RECOVERY AFTER PROSTATE CANCER: A NEED FOR MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

From a biological perspective, and for most men and couples, sexual recovery is not a return to baseline because most erectile dysfunction will persist at least to some degree. Therefore, managing expectations and helping couples communicate effectively about how to accept sexual changes while they continue to be sexually active under the new circumstances become important aspects of survivorship care. Preparing men and partners for sexual changes can help make those expectations more realistic and puts them on a more attainable path to sexual recovery.60 Preparation includes helping men and partners recognize the emotional aspects of the recovery. A normal response to loss (of function and familiar sexual activity) is grief and mourning. The role of grief and mourning as a gateway to sexual recovery after prostate cancer treatment has been described by Wittmann et al.64 Pillai-Friedman and Ashline, writing about breast cancer survivors, add the importance of re-eroticization of the body based on treatment related changes.65 Men and partners can attain a satisfying sex life if they can be flexible and expand their sexual repertoire beyond spontaneous penetrative sex.

Given the physical changes and emotional processes, sexual recovery will require collaboration among a number of disciplines. Therefore, providing survivorship care means referral to specialists such as mental health providers, certified sex therapists and physical therapists who can work collaboratively with the urologist who provides guidance for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, peyronie’s curvature and other physical side effects of prostate cancer treatment. Urologists who treat men for prostate cancer treatment related sexual side effects should be familiar with local specialists in pelvic floor rehabilitation and mental health. Locally available sex therapists can be found on the website of the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists (www.aasect.org).

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION OF SEXUAL HEALTH CARE IN PROSTATE CANCER SURVIVORSHIP

Despite the fact that sexual health support is increasingly recognized as an important aspect of survivorship care, few cancer centers or practices provide it. Several barriers impede its implementation.

Cost. In a review of the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) Medicare registry Pisu et al reported that the care of prostate cancer survivors between initial treatment and terminal care (ie when they are living with the side effects of treatment) costs approximately $3200 more on average than the health care for individuals without cancer, with end of life care reaching $62,000.66 Survivors cope with additional out of pocket expenses, including loss of work time, costs of transportation and employment disability. prostate cancer survivors may not have insurance coverage for pro-erectile medications, devices and mental health visits, all of which may be contributors to non-adherence to care and consequent lower quality of life.67 Despite the fact that there is now a cost-effective option, such as sildenafil,68 coverage of PDE5i has been fraught with challenges because they are seen as a pure quality of life drug. The AUA has advocated for coverage for PDE5i but Congress passed legislation barring use of federal funds for these medications by Medicaid (2005) and Medicare (2007). Since 2015 Medicare no longer covers the cost of vacuum erectile devices, and penile implant surgery requires at least 20% contribution for most patients. In contrast, Medicare does cover mental health, physical therapy and sex therapy visits.

Insufficient information about the needs of ethnic minorities. Despite the fact that the United States is a diverse country, there is almost no research on how sexual dysfunction after prostate cancer treatment affects non-white men. In a comprehensive review of several large studies Burnett reported that while African American men tend to have better erectile function recovery than their Caucasian counterparts, they are more bothered by sexual problems and are more willing to seek help for sexual rehabilitation,69 which may be due to the young age of African American men at diagnosis. Additional insights come from the study by Jenkins et al of 1112 Caucasian and 118 African American men treated with radical prostatectomy and radiation.70 Despite reporting a better recovery of sexual function than Caucasian men, African American men reported statistically significantly lower desire and perception that men could not have satisfying sex lives without an erection. Although the generalizability of this study is challenged by the low response rate of African American men versus Caucasian men (28% vs 51%), it raises a question worth pursuing with all cultural groups, which is what aspects of sexuality are valued and should be supported.

Lack of provider training. The IOM report recommended that educational opportunities be provided to arm health care providers with competencies to address survivorship care.3 To date, there is no evidence that education about survivorship care has been included in medical school, resident or fellowship curricula. Online cancer survivorship primers have attempted to address this gap in knowledge. Educational interventions, such as a continuing medical education intervention through Medscape Education across all relevant specialties (oncology, primary care, surgical subspecialties, psychiatry and mental health) or a 6-session Cancer Survivorship Workshop, integrated into the curriculum of hematology/oncology fellows and radiation oncology residents, resulted in improved knowledge of survivorship care and comfort in discussing survivorship issues with patients.71, 72 However, the study reports do not include sexual health content. Given the traditional discomfort with this topic by providers, it is unlikely that it was included.73Educating providers about sexuality and sexual health in cancer is a critical aspect of enabling competent survivorship care and should be integrated into medical school and oncology specialty training.

WHAT CAN SURGEONS DO?

It is not unusual for physicians to think that it is impossible to address the complex topic of sexuality in the course of a brief medical appointment in an oncology clinic. However, research in heart disease has shown that if patients are counseled about sexual health after a myocardial infarction, they are more likely to retain their sexual activity 1 year after the event.74 We know that when we speak to the patient with prostate cancer about sexual concerns, the partner, if available, should be present. Sex therapists use the PLISSIT (permission, limited information, specific suggestions and intensive therapy) model that guides the intensity of discussion about sexual concerns. This model, described in Appendix 4 (online issue only), begins with the simple opening of the conversation, giving permission to the patient to voice his sexual concerns.75 Limited information can include telling the patient and partner about the sexual side effects of treatment. Beyond limited information, addressing sexual issues can be referred to other specialists. Specific suggestions may include a discussion of pro-erectile aids as well as referrals to a nurse who will teach the use of erectile aids, to sex therapy for help with psychosexual adjustment after prostate cancer treatment or to a physical therapist who will address pelvic floor strengthening. Only a small number of patients will need a referral for intensive therapy when they report poor couple communication, preexisting conflict or sexual problems in the relationship, or depression/anxiety about the sexual problems.

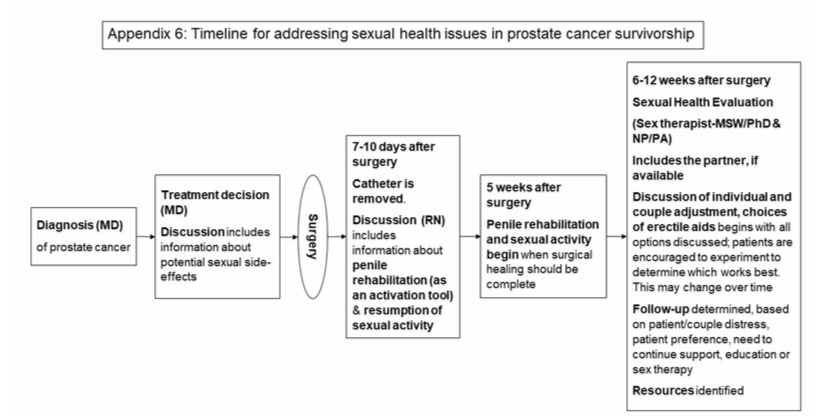

Using validated assessments can help start the conversation about sexual problems in prostate cancer survivorship. The AUA guidelines recommend the use of validated questionnaires to assess ED severity, measure efficacy of treatment and guide future management.40 Appendix 5 (online issue only) provides a list of assessments that have been used in research and clinical practice. Developing a timeline for sexual health conversations can guide urological care of patients with prostate cancer in survivorship. Inclusion of relevant disciplines can take place either within the urology practice or in collaboration with identified experts in the surrounding community (Appendix 6, online issue only).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND CHALLENGES

The need for sexual health care in prostate cancer survivorship is clearly articulated by patients, partners and health providers who care for these patients. However, there are significant gaps in knowledge and in methodologies for implementation. Research on the sexual health concerns of diverse ethnic and sexual minority groups is needed to enable tailoring of care to individual patients. In order to provide sufficient comprehensive care, advocacy to insurers by patients and providers is necessary to ensure coverage for erectile aids for those men who wish to use them. Finally, provider education about sexual issues in prostate cancer that goes beyond treating erectile dysfunction and surgical interventions will enable a more patient-oriented methodology for providing care in prostate cancer survivorship.

Appendix 1. Summary of common long-term and late effects of prostate cancer and its treatment (Reprinted with permission from Skolarus et al4)

| TREATMENT TYPE | LONG-TERM EFFECTS | LATE EFFECTS |

|---|---|---|

| Surgery (radical prostatectomy: open, laparoscopic, robotic assisted) | Urinary dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction

| Disease progression |

| Radiation (external beam or brachytherapy) | Urinary dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction

Bowel dysfunction

| Urinary dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction

Bowel dysfunction

|

| Hormone (androgen deprivation therapy) | Sexual dysfunction

|

|

| Expectant management (active surveillance or watchful waiting) |

|

|

| GENERAL PSYCHOSOCIAL LONG-TERM AND LATE EFFECTS |

|---|

|

Appendix 2. Population studies demonstrating sexual symptom burden after radical prostatectomy and radiation

| Study | Domains Evaluated | No. Patients | Time Points Evaluated | Sexual Dysfunction Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCOS (Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study) | Urinary, bowel, sexual | Radical prostatectomy 1164, radiotherapy 491 | Baseline, 6 + 12 months, 2, 5 + 15 years | Radical prostatectomy associated with greater odds of erectile dysfunction at 2 and 5 years |

| ProtecT (Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment) | Urinary, bowel, sexual | Radical prostatectomy 533, active monitoring 545, radiotherapy 545 | Baseline, 6 + 12 months, annually until 6 years | Radical prostatectomy had the greatest effect on sexual function; negative effect of radiotherapy greatest at 6 months, followed by recovery and stabilization period |

| CEASAR (Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation) | Urinary, bowel, sexual | Radical prostatectomy 1523, active surveillance 492,radiotherapy 598 | Baseline, 6, 12 + 36 months | Men who underwent radical prostatectomy had greatest decline in sexual function at 3 years |

Appendix 3. Pro-erectile aids: contraindications and adverse effects

| Pro-erectile Aid | Contraindications | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitors | Concurrent use of nitrates, myocardial infarction in the last 6 months | Vision abnormalities, headache, flushing, nasal congestion, hearing loss, upset stomach, priapism, back pain, myalgia |

| Intraurethral suppositories (medicated urethral systems for erection) | Significant cardiac disease; history of sickle cell anemia, leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, penile curvature, penile implant, hypospadias and prostaglandin allergy/hypersensitivity; contraindicated in use for sexual intercourse with pregnant partner unless condom barrier is used. | Penile pain, urethral pain/burning, testicular pain, urethral bleeding/spotting, hypotension, dizziness, back pain, leg pain, headache, rhinitis |

| Intracavernosal injections | Significant cardiac disease; history of priapism, sickle cell anemia or trait, thrombocytopenia, hyperviscosity syndrome, leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, penile deformities and penile prosthesis, hypersensitivity to agent | Bruising, hematoma/ecchymosis; penile, urethral, testicular, back and leg pain; headache; hypotension; dizziness; penile rash;vision impairment; priapism; cold symptoms |

| Vacuum erection device | Use of blood thinners, bleeding disorder, sickle cell anemia, disorder that predisposes to priapism | Bruising, decrease in ejaculation force |

| Penile prosthesis | Relative: uncontrolled diabetes mellitus | Infection, mechanical failure, erosion |

Appendix 4. PLISSIT model

| Statement (choose, based on relevance) | Meaning to Patient | |

|---|---|---|

| Permission |

|

|

| Limited Information |

|

|

| Specific Suggestions |

| There is something that can be done |

| Intensive Therapy |

|

|

Appendix 5. Validated sexual health measures

| Measure Name | References | Domains (No. items) |

|---|---|---|

| EPIC (Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite-Short Form) | Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS et al: Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 2000; 56: 899. | Sexual, Urinary, Bowel, Hormonal (26) |

| SHIM (Sexual Health Inventory for Men) | Cappelleri JC and Rosen RC: The Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM): a 5-year review of research and clinical experience. Int J Impot Res 2005; 17: 307. | Sexual (5) |

| IIEF (International Index of Erectile Function) | Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC and Gendrano N 3rd: The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a state-of-the-science review. Int J Impot Res 2002; 14: 226. | Sexual (15) |

| PROMIS® (Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System) Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measures | Weinfurt KP, Lin L, Bruner DW et al: Development and initial validation of the PROMIS(®) Sexual Function and Satisfaction measures version 2.0. J Sex Med 2015; 12: 1961. | Erectile Function (8), Global Satisfaction with Sex Life (7), Interest in Sexual Activity (4), Anal Discomfort (5), Interfering Factors (10), Orgasm (3), Therapeutic Aids (9), Sexual Activities (12) |

Appendix 6. Timeline for addressing sexual health issues in prostate cancer survivorship

REFERENCES

- Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67: 7.

- Office of Cancer Survivorship: Survivorship Definitions. Bethesda, Maryland: National Cancer Institute 2014. Available at https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/statistics/ definitions.html.

- Committee on Cancer Survivorship: From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Edited by M Hewitt, S Greenfield and E Stovall. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press 2006.

- Skolarus TA, Wolf AM, Erb NL et al: American Cancer Society Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care Guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64: 225.

- Bernat JK, Skolarus TA, Hawley ST et al: Negative information-seeking experiences of long-term prostate cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2016; 10: 1089.

- U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group: Leading Cancer Cases and Deaths, Male, 2015. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2018. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/data/men.htm.

- Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan KH et al: Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 436.

- Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA et al: Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1425.

- Barocas DA, Alvarez J, Resnick MJ et al: Association between radiation therapy, surgery, or observation for localized prostate cancer and patient-reported outcomes after 3 years. JAMA 2017; 317: 1126.

- Capogrosso P, Vertosick EA, Benfante NE et al: Are we improving erectile function recovery after radical prostatectomy? Analysis of patients treated over the last decade. Eur Urol 2019; 75: 221.

- Shaikh T, Li T, Handorf EA et al: Long-term patient-reported outcomes from a phase 3 randomized prospective trial of conventional versus hypofractionated radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017; 97: 722.

- Bolla M, Maingon P, Carrie C et al: Short androgen suppression and radiation dose escalation for intermediate and high-risk localized prostate cancer: results of EORTC Trial 22991. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 1748.

- Fode M and Sonksen J: Sexual function in elderly men receiving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Sex Med Rev 2014; 2: 36.

- Huang GJ, Sadetsky N and Penson DF: Health related quality of life for men treated for localized prostate cancer with long-term followup. J Urol 2010; 183: 2206.

- Potosky AL, Knopf K, Clegg LX et al: Quality-of-life outcomes after primary androgen deprivation therapy: results from the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3750.

- Fode M, Serefoglu EC, Albersen M et al: Sexuality following radical prostatectomy: is restoration of erectile function enough? Sex Med Rev 2017; 5: 110.

- Tran SN, Wirth GJ, Mayor G et al: Prospective evaluation of early postoperative male and female sexual function after radical prostatectomy with erectile nerves preservation. Int J Impot Res 2015; 27: 69.

- Salomon G, Isbarn H, Budaeus L et al: Importance of baseline potency rate assessment of men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer prior to radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med 2009; 6: 498.

- Chambers SK, Ng SK, Baade P et al: Trajectories of quality of life, life satisfaction, and psychological adjustment after prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2017; 26: 1576.

- Bober SL and Varela VS: Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 3712.

- Hedestig O, Sandman PO, Tomic R et al: Living after radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer: a qualitative analysis of patient narratives. Acta Oncol 2005; 44: 679.

- Ervik B and Asplund K: Dealing with a troublesome body: a qualitative interview study of men’s experiences living with prostate cancer treated with endocrine therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012; 16: 103.

- Wall D and Kristjanson L: Men, culture and hegemonic masculinity: understanding the experience of prostate cancer. Nurs Inq 2005; 12: 87.

- Sanders S, Pedro LW, Bantum EO et al: Couples surviving prostate cancer: long-term intimacy needs and concerns following treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2006; 10: 503.

- Tsivian M, Mayes JM, Krupski TL et al: Altered male physiologic function after surgery for prostate cancer: couple perspective. Int Braz J Urol 2009; 35: 673.

- Wittmann D, Carolan M, Given B et al: Exploring the role of the partner in couples’ sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 2014; 22: 2509.

- Ramsey SD, Zeliadt SB, Blough DK et al: Impact of prostate cancer on sexual relationships: a longitudinal perspective on intimate partners’ experiences. J Sex Med 2013; 10: 3135.

- InstituteofMedicine:TheHealthofLesbian,Gay,Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press 2011.

- Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office: Sexual and Gender Minority Research Portfolio Analysis. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health 2016. Available at https:// dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/SGMRO_2016_Portfolio_Analysis_Final.pdf.

- Ussher JM, Perz J, Kellett A et al: Health-related quality of life, psychological distress, and sexual changes follow- ing prostate cancer: a comparison of gay and bisexual men with heterosexual men. J Sex Med 2016; 13: 425.

- Montorsi F, Guazzoni G, Strambi LF et al: Recovery of spontaneous erectile function after nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy with and without early intracavernous injections of alprostadil: results of a prospective, randomized trial. J Urol 1997; 158: 1408.

- Hu WL, Hu LQ, Song J et al: Fibrosis of corpus cavernosum in animals following cavernous nerve ablation. Asian J Androl 2004; 6:111.

- Vignozzi L, Morelli A, Filippi S et al: Effect of sildenafil administration on penile hypoxia induced by cavernous neurotomy in the rat. Int J Impot Res 2008; 20: 60.

- Fode M, Borre M, Ohl DA et al: Penile vibratory stimulation in the recovery of urinary continence and erectile function after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: a randomized, controlled trial. BJU Int 2014; 114: 111.

- Fode M, Ohl DA, Ralph D et al: Penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy: what the evidence really says. BJU Int 2013; 112: 998.

- Philippou YA, Jung JH, Steggall MJ et al: Penile rehabilitation for postprostatectomy erectile dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; doi: 10.1002/14651858.

- Raina R, Agarwal A, Ausmundson S et al: Early use of vacuum constriction device following radical prostatec- tomy facilitates early sexual activity and potentially earlier return of erectile function. Int J Impot Res 2006; 18: 77.

- Bannowsky A, Schulze H, van der Horst C et al: Recovery of erectile function after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: improvement with nightly low-dose sildenafil. BJU Int 2008; 101: 1279.

- Salonia A, Adaikan G, Buvat J et al: Sexual rehabilitation after treatment for prostate cancer-part 2: recommendations from the Fourth International Consultation for Sexual Medicine (ICSM 2015). J Sex Med 2017; 14: 297.

- Burnett AL, Nehra A, Breau RH et al: Erectile Dysfunction: AUA Guideline. J Urol 2018; 200: 633.

- Wang X, Wang X, Liu T et al: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors for treatment of erectile dysfunction following bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. PloS One 2014; 9: e91327.

- Montorsi F, Brock G, Stolzenburg JU et al: Effects of tadalafil treatment on erectile function recovery follow- ing bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: a ran- domised placebo-controlled study (REACTT). Eur Urol 2014; 65: 587.

- Hanisch LJ, Bryan CJ, James JL et al: Impact of sildenafil on marital and sexual adjustment in patients and their wives after radiotherapy and short-term androgen suppression for prostate cancer: analysis of RTOG 0215. Support Care Cancer 2012; 20: 2845.

- Ricardi U, Gontero P, Ciammella P et al: Efficacy and safety of tadalafil 20 mg on demand vs. tadalafil 5 mg once-a-day in the treatment of post-radiotherapy erectile dysfunction in prostate cancer men: a randomized phase II trial. J Sex Med 2010; 7: 2851.

- Watkins Bruner D, James JL, Bryan CJ et al: Randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled crossover trial of treat- ing erectile dysfunction with sildenafil after radiotherapy and short-term androgen deprivation therapy: results of RTOG 0215. J Sex Med 2011; 8: 1228.

- Incrocci L, Koper PC, Hop WC et al: Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) and erectile dysfunction following external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2001; 51: 1190.

- Harrington C, Campbell G, Wynne C et al: Randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of sildenafil citrate in the treatment of erectile dysfunction following external beam radiation treatment of prostate cancer. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2010; 54: 224.

- Raina R, Agarwal A, Zaramo CE et al: Long-term efficacy and compliance of MUSE for erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy: SHIM (IIEF-5) analysis. Int J Impot Res 2005; 17: 86.

- Raina R, Nandipati KC, Agarwal A et al: Combination therapy: medicated urethral system for erection enhances sexual satisfaction in sildenafil citrate failure following nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. J Androl 2005; 26: 757.

- Coombs PG, Heck M, Guhring P et al: A review of outcomes of an intracavernosal injection therapy programme. BJU Int 2012; 110: 1787.

- Nelson CJ, Hsiao W, Balk E et al: Injection anxiety and pain in men using intracavernosal injection therapy after radical pelvic surgery. J Sex Med 2013; 10: 2559.

- Nandipati K, Raina R, Agarwal A et al: Early combination therapy: intracavernosal injections and sildenafil following radical prostatectomy increases sexual activity and the return of natural erections. Int J Impot Res 2006; 18: 446.

- Engel JD: Effect on sexual function of a vacuum erection device post-prostatectomy. Can J Urol 2011; 18: 5721.

- Megas G, Papadopoulos G, Stathouros G et al: Comparison of efficacy and satisfaction profile, between penile prosthe- sis implantation and oral PDE5 inhibitor tadalafil therapy, in men with nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy erectile dysfunction. BJU Int 2013; 112: E169.

- Tal R, Jacks LM, Elkin E et al: Penile implant utilization following treatment for prostate cancer: analysis of the SEER-Medicare database. J Sex Med 2011; 8: 1797.

- Miller DC, Wei JT, Dunn RL et al: Use of medications or devices for erectile dysfunction among long-term prostate cancer treatment survivors: potential influence of sexual motivation and/or indifference. Urology 2006; 68: 166.

- Titta M, Tavolini IM, Dal Moro F et al: Sexual counseling improved erectile rehabilitation after non-nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy or cystectomy—results of a randomized prospective study. J Sex Med 2006; 3: 267.

- Chambers SK, Occhipinti S, Schover L et al: A randomised controlled trial of a couples-based sexuality intervention for men with localised prostate cancer and their female partners. Psychooncology 2015; 24: 748.

- Wittmann D: Emotional and sexual health in cancer: partner and relationship issues. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2016; 10: 75.

- Paich K, Dunn R, Skolarus T et al: Preparing patients and partners for recovery from the side effects of prostate cancer surgery: a group approach. Urology 2016; 88: 36.

- Walker LM, Hampton AJ, Wassersug RJ et al: Androgen deprivation therapy and maintenance of intimacy: a ran- domized controlled pilot study of an educational intervention for patients and their partners. Contemp Clin Trials 2013; 34: 227.

- Skolarus TA, Metreger T, Hwang S et al: Optimizing veteran-centered prostate cancer survivorship care: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017; 18: 181.

- Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y et al: A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer 2012; 118: 500.

- Wittmann D, Foley S and Balon R: A biopsychosocial approach to sexual recovery after prostate cancer surgery: the role of grief and mourning. J Sex Marital Ther 2011; 37: 130

- Pillai-Friedman S and Ashline JL: Women, breast cancer survivorship, sexual losses, and disenfranchised grief—a treatment model for clinicians. Sex Relation Ther 2014; 29: 436

- Pisu M, Henrikson NB, Banegas MP et al: Costs of cancer along the care continuum: what we can expect based on recent literature. Cancer 2018; 124: 4181.

- Teloken P, Mesquita G, Montorsi F et al: Post-radical prostatectomy pharmacological penile rehabilitation: practice patterns among the International Society for Sexual Medicine practitioners. J Sex Med 2009; 6: 2032.

- Smith KJ and Roberts MS: The cost-effectiveness of sildenafil. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132: 933.

- Burnett AL: Racial disparities in sexual dysfunction out-comes after prostate cancer treatment: myth or reality? J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2016; 3: 154.

- Jenkins R, Schover LR, Fouladi RT et al: Sexuality and health-related quality of life after prostate cancer in African-American and white men treated for localized disease. J Sex Marital Ther 2004; 30: 79.

- Buriak SE and Potter J: Impact of an online survivorship primer on clinician knowledge and intended practice changes. J Cancer Educ 2014; 29: 114.

- Shayne M, Culakova E, Milano MT et al: The integration of cancer survivorship training in the curriculum of hematology/oncology fellows and radiation oncology residents. J Cancer Surviv 2014; 8: 167.

- Gilbert E, Perz J and Ussher JM: Talking about sex with health professionals: the experience of people with cancer and their partners. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016; 25: 280.

- Lindau ST, Abramsohn E, Bueno H et al: Sexual activity and function in the year after an acute myocardial infarction among younger women and men in the United States and Spain. JAMA Cardiol 2016; 1: 754.

- Ayaz S and Kubilay G: Effectiveness of the PLISSIT model for solving the sexual problems of patients with stoma. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18: 89.